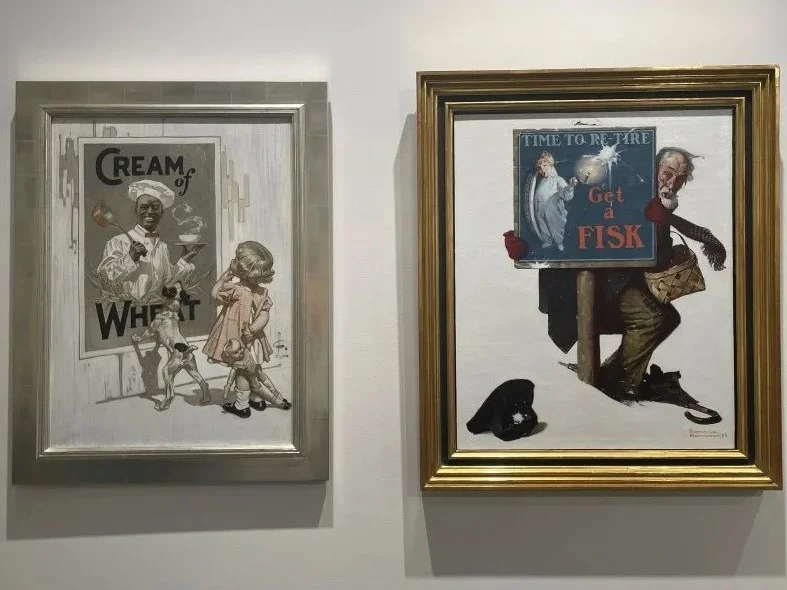

Norman Rockwell & J.C. Leyendecker

Norman Rockwell

(1894–1978)

Born in New York City, Rockwell spent his childhood and adolescence there, with significant summer excursions into the country. He felt a strong sense of connectedness not only with nature, but also with the people who had chosen to live “on nature’s terms”. Rockwell’s early inspiration to draw and paint came from his father, an avid Sunday painter. It also came indirectly from his grandfather’s primitive canvases of bucolic barnyard scenes. He studied painting at the newly formed Arts Students League where he was taught anatomical accuracy by George Bridgman and learned composition from Thomas Fogarty.

The most popular and fashionable illustrators of the time, N.C. Wyeth, J.C. Leyendecker, Maxfield Parrish and Howard Pyle, were powerful influences on Norman Rockwell’s development as an artist. His admiration for J.C. Leyendecker was obsessive. In 1915, after completing his studies in New York City, Rockwell moved to New Rochelle just to be near Leyendecker.

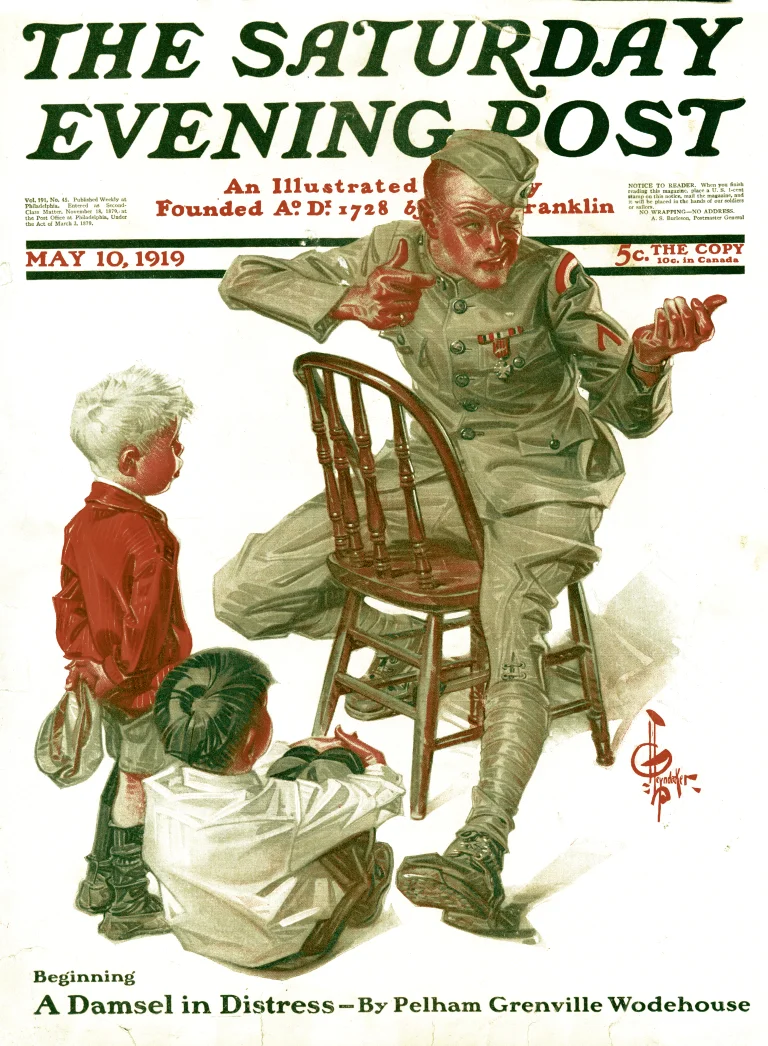

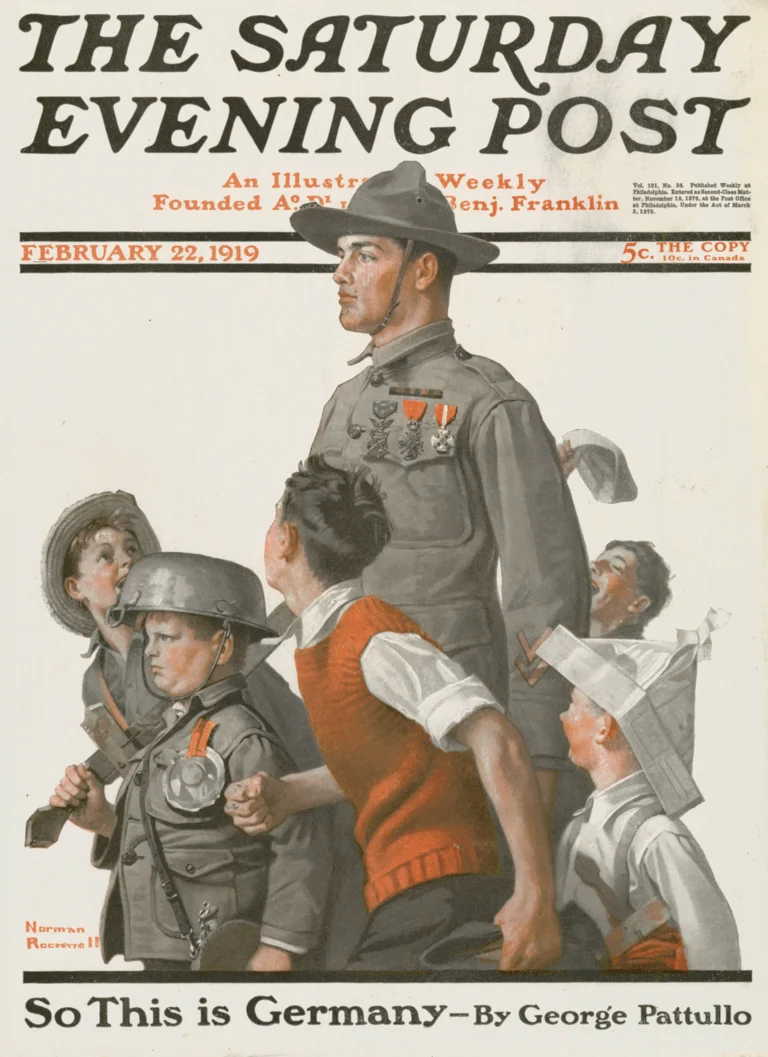

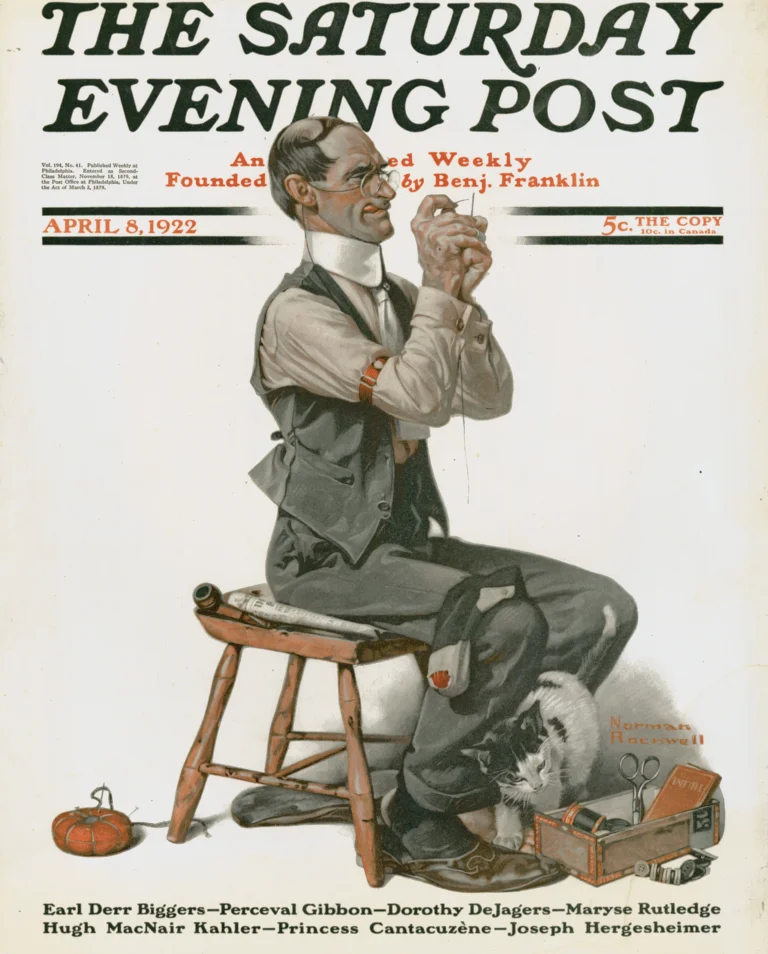

At 22 Rockwell sold his first cover piece to The Saturday Evening Post—a prized commission for an illustrator. It was the beginning of a 323-cover relationship between Rockwell and the Post.

In a sense, Rockwell was the last of the 19th-century genre painters, but one who came into his creative powers at a time when a new audience and market was opening up. Mass-circulated national magazines with great popularity catapulted certain artists into millions of households weekly and Rockwell clearly had the right talent at the right time. In the 1920s and 1930s, his work developed great breadth and greater character. His use of humor became an important part of his work. It was a technique he used effectively to draw the viewer into the composition to share the magic.

Rockwell was constantly seeking new ideas and new faces in his daily life. He wrote that everything he had ever seen or done had gone into his pictures. His internal art of ‘storytelling’ became integrated with his external skills as an artist. What emerged was what we know today as an incredible facility in judging the perfect moment; when to stop the action, snap the picture…when all the elements that define and embellish a total story are in place.

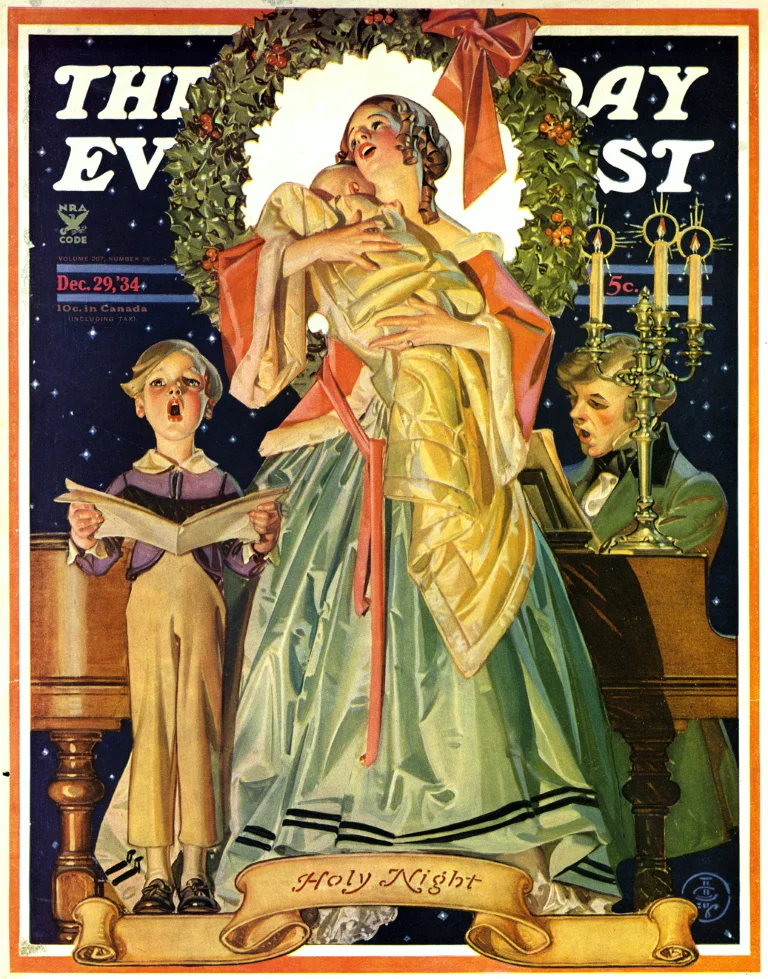

In 1936, Editor George Horace Lorimer retired from The Saturday Evening Post, and the second of two successive editors, Ben Hibbs, altered the circular format of the cover. Hibbs permitted Norman Rockwell to create with more freedom within a different cover layout.

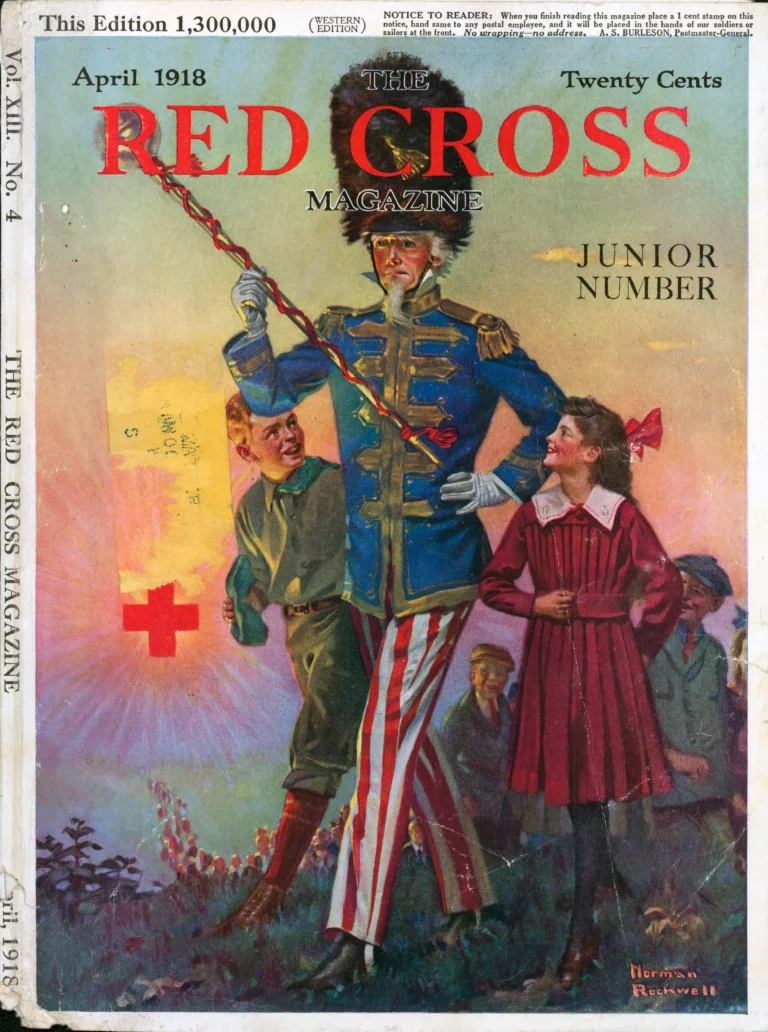

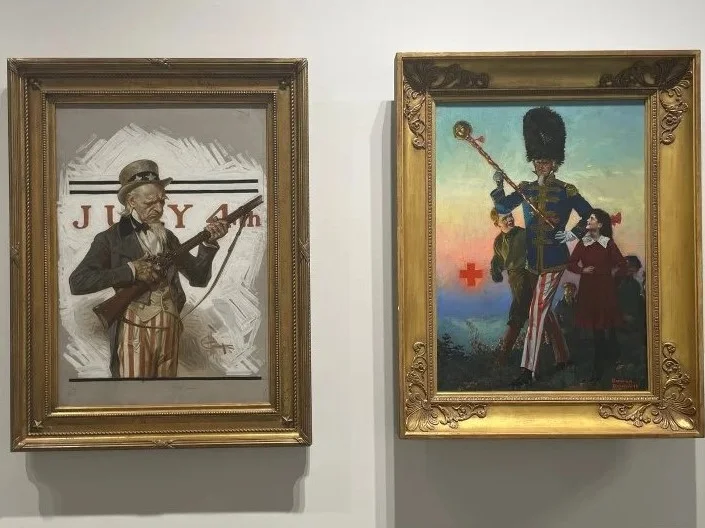

In the 1940s, Rockwell moved to Arlington, Vermont, where he started to paint the full-canvas paintings that are increasingly treasured by collectors. During World War II, Rockwell joined the legion of artists and writers involved in the war effort to help boost the sale of savings bonds. He tried to explain through his art what the war was all about. The result of his efforts was the series called ‘The Four Freedoms’: first rejected by the US Government, then printed as posters to sell war bonds.

In the 1960s, from his home in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, Rockwell struck out in a new direction. Though by then his reputation was rooted in the evocation of nostalgia, he boldly tackled political issues. The Peace Corps in Ethiopia captured the idealism of the Kennedy years in a realistic setting.

Rockwell’s work truly reflected the currents of American life and times, from his earliest drawings to the patriotic themes of World War II to more politically oriented themes in his later years. His genius was in being able to capture the essence of what is now considered largely “an America vanished”. His Post covers captured the emotions of the times, not only that which was, but also what people would have liked life to be. Yet one look at an original Rockwell painting will make apparent the quality of his technique, style, and craftsmanship.

J.C. Leyendecker

(1874 – 1951)

Joseph Christian Leyendecker developed as a major talent near the turn of the twentieth century and became the most in vogue American illustrator of his day. JC Leyendecker was a keen student of self-promotion and quickly established an easily identifiable style, reaching the peak of his fame and productivity in the 1930’s. Leyendecker’s approach to his career influenced the art of illustration and he became mentor to an entire generation of younger artists, most notably Norman Rockwell, who began his career by specifically emulating Leyendecker.

J.C. Leyendecker and his younger brother Francis Xavier Leyendecker (F.X.), were born in Montabour, Germany, and moved to America in 1882. Joe and Frank (also an aspiring illustrator) studied in Paris at the Academie Julian, where they developed their artistic visions.

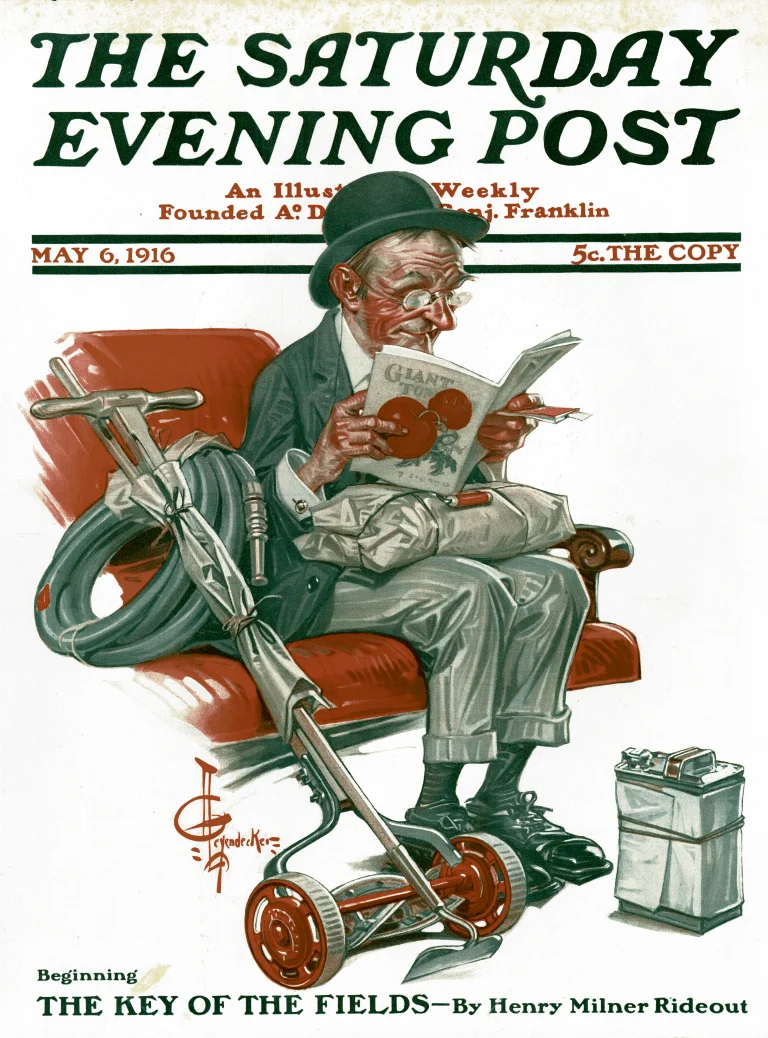

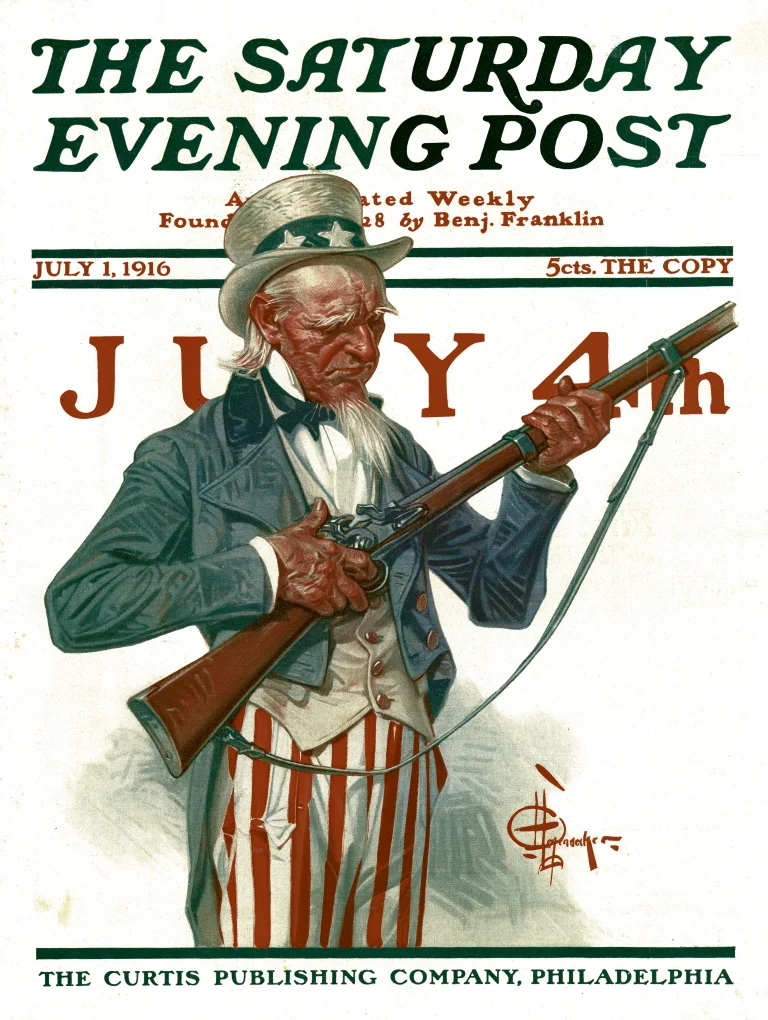

Between 1896 and 1950, J.C. Leyendecker painted more than four hundred magazine covers. During “The Golden Age of American Illustration”, the Saturday Evening Post alone commissioned J.C. Leyendecker to produce 322 covers as well as many advertisement illustrations for its interior pages. No other artist, until the arrival of Norman Rockwell two decades later, was so solidly identified with one publication.

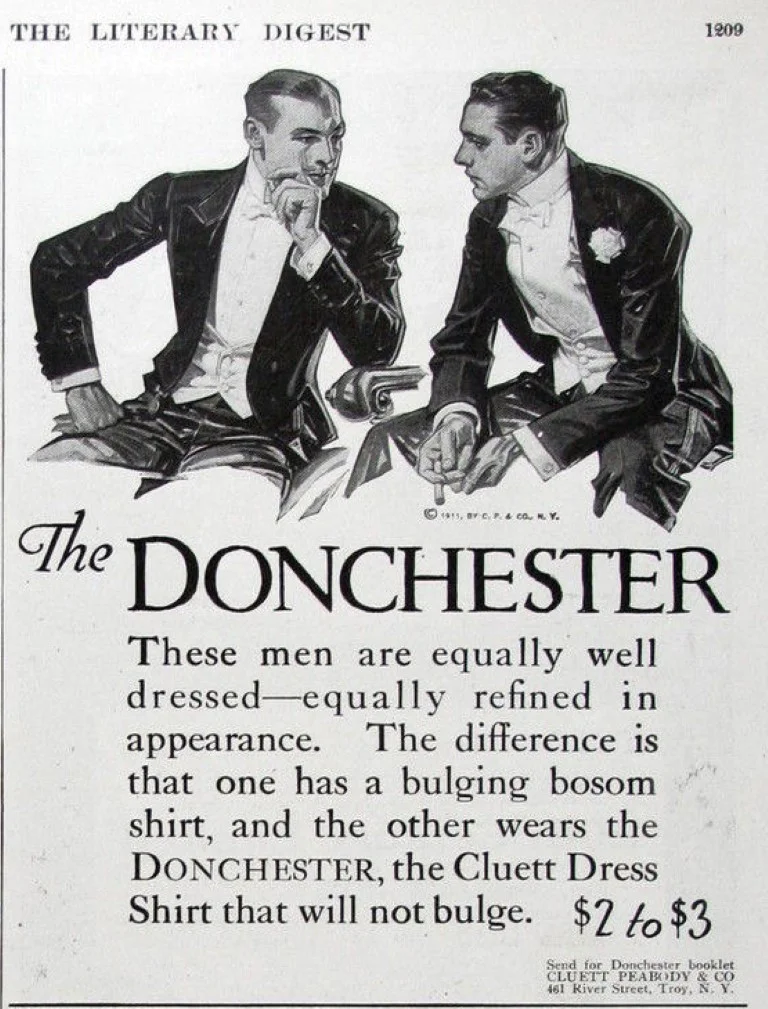

Joe Leyendecker’s renown grew from his ability to establish a specific and readily identifiable signature style. With very wide, deliberate strokes done with authority and control, he seldom overpainted, preferring to interest the viewer with the omissions as well as parts included. His three most memorable creations, which live on to this day, were the iconic images of the Arrow Collar Man advertisements, the New Year’s Baby, and the first Mother’s Day magazine cover created for the Post. The May 30, 1914 Post Mother’s Day cover single-handedly birthed the flower delivery industry, and it created an American tradition.

In 1905, Leyendecker received what became his most important commercial art commission when he was hired by Cluett, Peabody & Co. to advertise their Arrow detachable shirt collars. Leyendecker created the ‘Arrow Collar Man,’ handsome and smartly dressed; he became the symbol of fashionable American manhood and the first brand in advertising. Through his ads, Leyendecker boosted sales for the company to over $32 million per year, and defined the ideal American male: a dignified, clear-eyed man of taste, manners and quality.

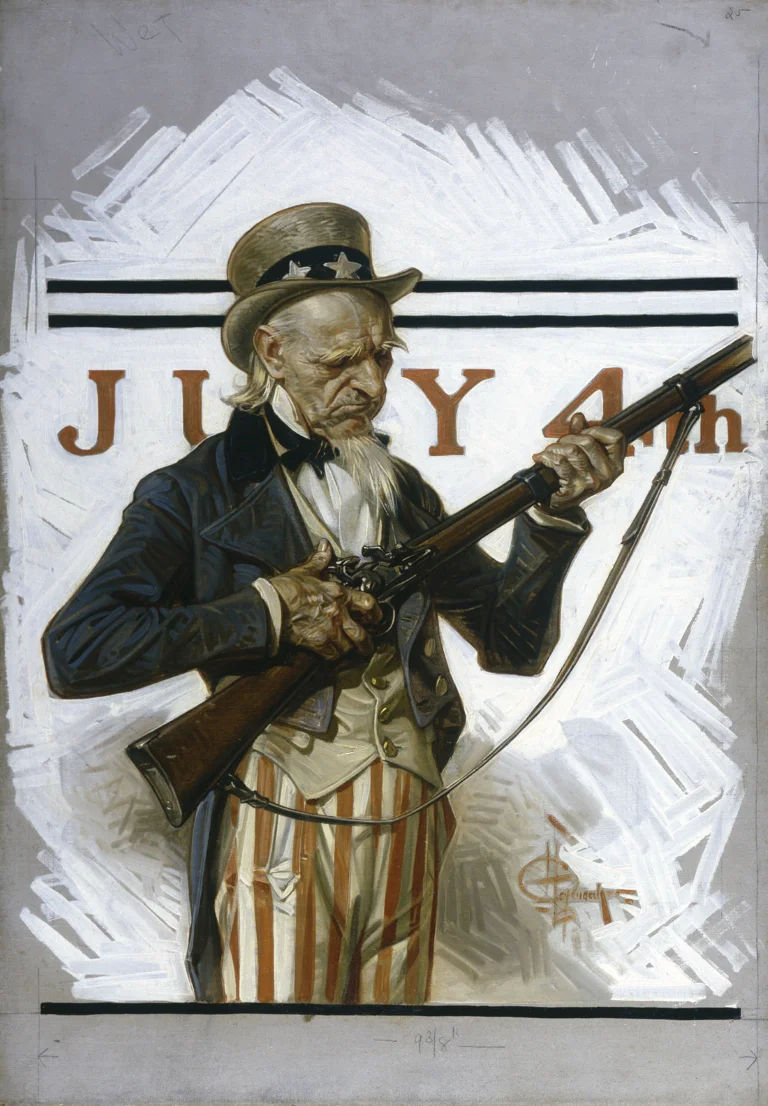

As the Saturday Evening Post’s most important cover artist of his day, J.C. Leyendecker illustrated all the holiday numbers, as well as many in-between. His Easter, Independence Day, Thanksgiving and Christmas covers were annual events for the Post’s millions of readers. Leyendecker gave us what is perhaps the most enduring New Year’s symbol, that of the New Year’s Baby. For almost forty years, the Post featured a Leyendecker Baby on its New Year’s covers.

Leyendecker illustrated American heroes in both sports and on battlefields. He designed posters for World War I and World War II efforts and in the process, inspired Americans to support the cause. His sports posters, painted often to promote Ivy League football, baseball and crew teams, were widely collected by college students. All through his career, his favorite model was his companion of 50 years, Charles A. Beach. Beach was a Canadian fan whom Leyendecker met in 1901, and immortalized as the ‘Arrow Collar Man.’

The broad range of JC Leyendecker’s career included advertisements for The House of Kuppenheimer, Ivory Soap, and Kelloggs, as well as magazine covers for such publications as Collier’s and Success. He greatly influenced the art of illustration, and positioned himself as a mentor to a younger generation of illustrators, most notably Norman Rockwell. In many ways, JC Leyendecker was the personification of The American Imagist, an illustrator whose images came to symbolize so much in our American civilization.