Warner Bros.

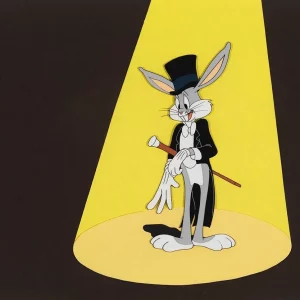

Within the last few decades, the Warner Bros. cartoon studio has earned both critical and popular acclaim as the producers of the finest, funniest, and most inventive animated shorts ever made. The Hollywood studio, which opened in 1930 and shut its theatrical division in 1969, developed and perfected the kind of antic, irreverent, street-smart humor that has characterized much of short-subject animation ever since. Along the way, the Warner shop won six Academy Awards, and created more cartoon stars than any other studio – in chronological order, Porky Pig, Daffy Duck, Elmer Fudd, Bugs Bunny, Tweety, Pepe Le Pew, Sylvester, Yosemite Sam, Foghorn Leghorn, The Road Runner, Wile E. Coyote, Speedy Gonzales, and many others.

Originally produced for screening in theaters, the studio’s cartoons are now shown on television hundreds of times a day all around the world; its more than 1,000 titles constitute what can only be considered a library of modern folklore.

More so than any other animated shorts, the Warner cartoons have infiltrated the fabric of American life. Since the studio hit its stride, after the introduction of Porky Pig in 1935, its cartoons have never been less than enormously popular. In the heyday of theatrical animation, Warner cartoons were voted America’s most popular shorts for 16 consecutive years – from 1945 to 1960. Even now, some 80 years after his creation, Bugs Bunny continues to win major national popularity polls.

Such Warnerisms as Bugs Bunny’s “What’s up, Doc?,” Porky Pig’s “That’s all, folks!,” and Tweety’s “I Taut I Taw a Putty-tat!” have earned places in the national patois. And even such lesser turns as Sylvester’s “Sufferin’ succotash!” and Bugs Bunny’s jeered “What a maroon!” have entered the repertory – not to mention that mythical manufacturer of anything-a-Coyote-ever-needs called “Acme.” The influence of characters, styles of humor, notions of pacing, and narrative devices introduced by Warner cartoons can be felt in many corners of popular culture – film, television, and even literature.

Yet despite the cartoons’ popularity, critical attention during Warner Bros’ finest years of production was virtually non-existent. Cartoons – fast, funny, and anti-authoritarian – were never deemed worthy of serious consideration. In 1943, however, critic Manny Farber wrote in The New Republic about the Warner cartoons that “The surprising facts about them are that the good ones are masterpieces and the bad ones aren’t a total loss.”

All this had changed by the mid-1970s. With the help of an ally called television, the Warner cartoons, like Chaplin and Keaton before them, were massively rediscovered. Film students and critics were stunned by the cartoons’ sophistication and cinematic savvy. In major articles, Time magazine called the Warner cartoonists “some of the top film artists and pleasure givers of the past half century,” while The Washington Post described them as “men who well may qualify as among the century’s great humorists, [who] made an invaluable contribution to the culture that only in recent years has begun to receive the outpourings of appreciation it deserves.”

What differentiated the Warner cartoons can be summed up in the words of longtime Warner story man Michael Maltese: “We wrote cartoons for grownups, that was the secret.”

Under the early influence of the Disney studio, animation had virtually become a children’s affair, soft and sentimental and story-bookish. Warner Bros. turned this on its head, making cartoons that were brash and reckless and filled with topical references, bringing animation from never-never land into the thick of contemporary life.

With striking frequency, the Warner writers devised stories and gags of brilliant invention, while the studio’s directors executed them with masterly verve and timing. They, in turn, were supported by a cadre of gifted animators, painters, and designers. The result is a body of work that, with each new screening, seems richer and deeper, and more clearly a significant part of American culture.